Let’s address that elephant in the room. We know what you’re thinking: BioShock isn’t a retro game. It’s a fair standpoint, but the underwater FPS celebrated its 15th anniversary in August, which falls within our own remit, and regardless, no one can discount its status as an utter classic. And the fact is, when it comes to selecting games from the pile of ‘recently retro’ to cover, only the very best, most innovative, most impactful games can make the cut… and that basically defines BioShock. But what’s interesting about the game’s development is how so much of its essence is owed to a much older, equally beloved release.

«We didn’t think we were done with some of the ideas that we worked with on System Shock 2 and we wanted to keep working in that genre,» says Jonathan Chey. Many will know Jon as one of the co-founders of Irrational Games, and he was the director of development on the game. «We didn’t feel that anyone had picked up on those ideas. At least for the next few years after it had been released, there wasn’t a flood of System Shock 2 clones on the market because it hadn’t been a huge hit. So we didn’t feel like that space had really still been explored. We felt that it deserved to be more popular than it was.»

Little Sisters

Subscribe today

This feature first appeared in Retro Gamer magazine. For more in-depth features exploring classic games and consoles delivered right to your door or device, subscribe to Retro Gamer (opens in new tab) in print or digital.

This was actually one of the driving forces behind the creation of BioShock, the team’s desire to create something like System Shock 2, but something that could have a much broader appeal. «We recognised that there were things in System Shock 2 that were holding it back, that were excessively complicated, that were opaque or hard for people to understand or that they simply didn’t like.» Jon lists fiddly controls, excessive menu navigation and a reliance on mouse and keyboard input as just some of the things that needed fixing if they wanted BioShock to become mainstream.

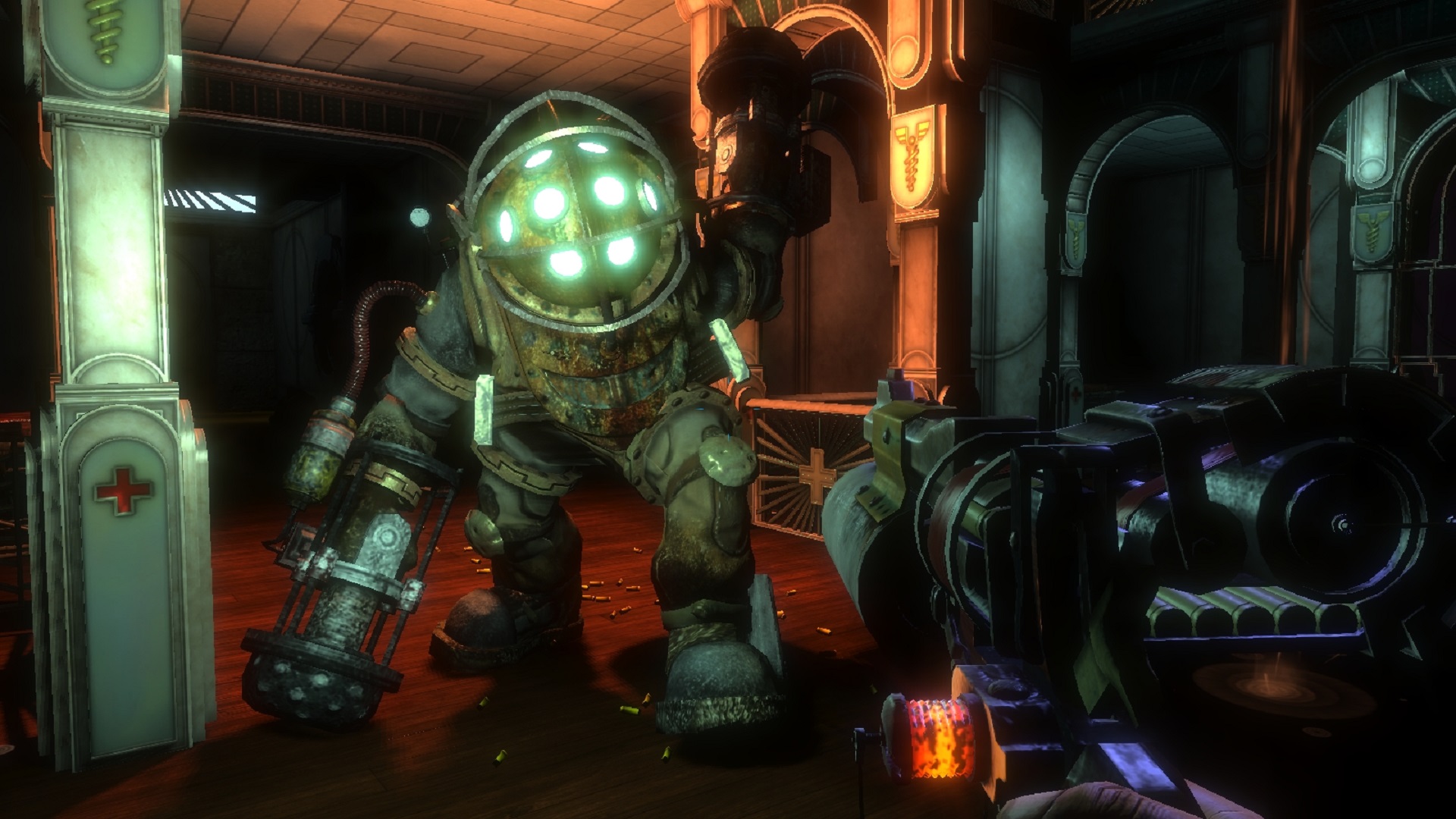

Irrational Games often pitched itself as a design-led studio, and that it intended to focus first on the mechanisms of the game rather than any storyline element. At the very start of it all, ahead of any existente plan or prototyping, was a gameplay system that many might recognise. Essentially it boiled down to three archetypes of NPCs: drones, protectors and harvesters. This equated to characters in the game that would transport something valuable, protectors that would help them do it, and the latter that would seek to relinquish this resource for themselves.

«The diferente idea for the Little Sisters was a mechanical one,» explains Jon, «which was that there would be creatures who were essentially mobile treasure chests and they would be guarded by other creatures. The mobile treasure chest would walk around the level doing something, and there would be something else watching over them. But what those things were wasn’t established for quiebro a long time.»

The idea was to create systems that worked together to create something that seemed existente and believable, as though the world of the game would trundle along with or without the player. «So that’s where the Little Sisters, the Big Daddies and the Splicers come from,» explains Jon. «We had some monsters that weren’t just about how they fight you, what’s interesting about them is that they interact with each other and there are different ways that you can interact with them that isn’t just about what the best angle to shoot them from is.»

It was quiebro some time before they took on the iconic look of a possessed girl and her accompanying boring drill with legs, however, which organically evolved as development of the story progressed. «Originally the Little Sisters were called Gatherers, and they went through a number of iterations,» Jon says. «At one stage they were like slugs that crawled around sucking things out of corpses, there was a whole range. It was a long time before they were the little girls we ended up with.»

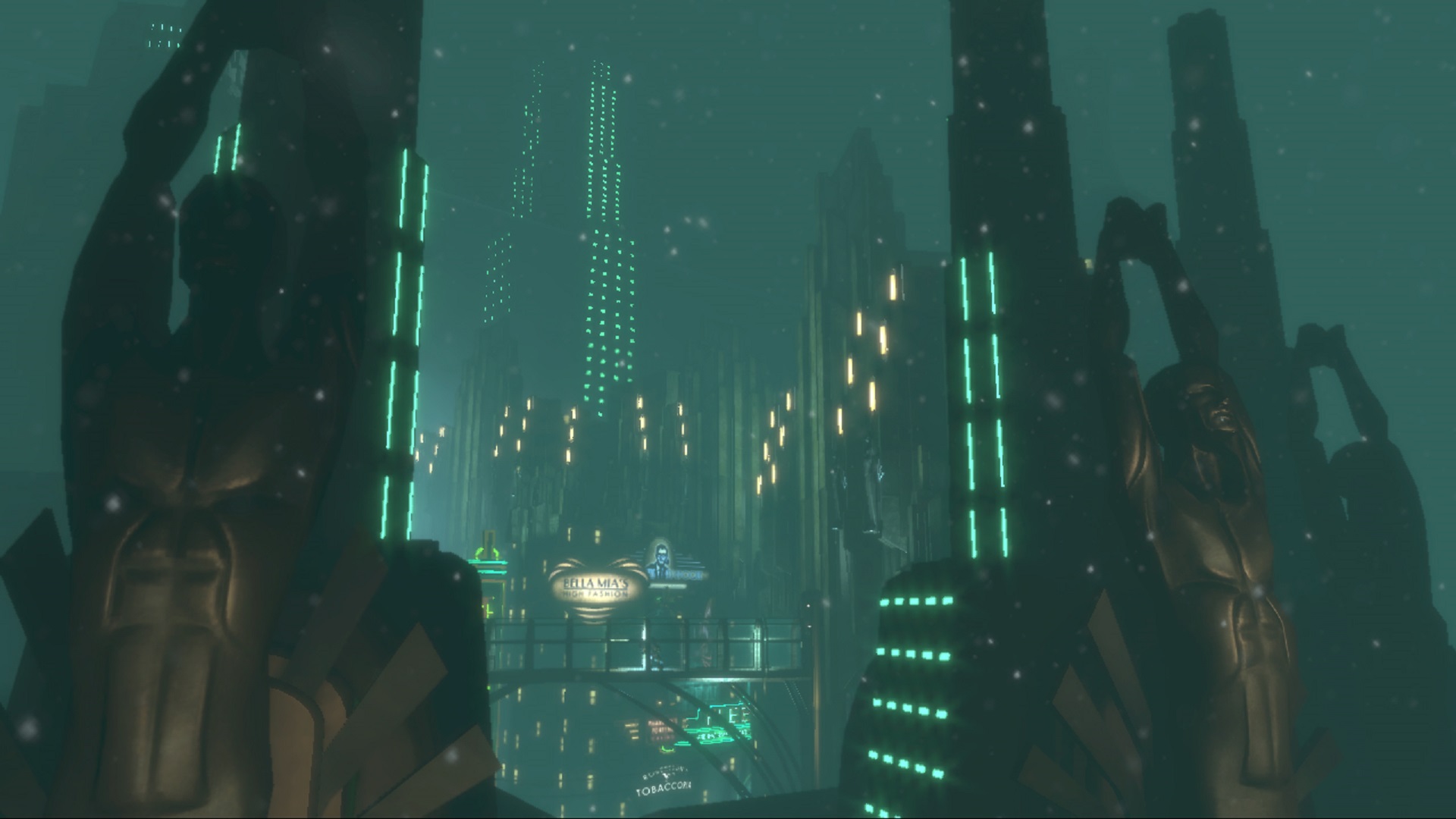

Finding Rapture

This was true of the final setting of the game, as well, which was originally built around something fairly akin to System Shock. Aboard a space station, the player would battle against genetically modified mutants while rescuing other characters from cults all bundled into a dark story covering political topics. The team ultimately turned its back on the concept, and so Ken Levine – the reputed writer of BioShock – came up with something else.

«It was set on an island after the Second World War,» recalls Jon of what would be the foundation for BioShock’s story. «It was a secret Fascista saco that had been set up during the war. It had been abandoned and now it’s full of crazy Nazis and the results of their crazy experiments. It obviously had some things in common, you can see how he got from there to the underwater Ayn Randian fantasy paradise gone bad. It changed a lot along the way, obviously.»

As we know, the final thematic change came along, in part thanks to 2K Games buying out Irrational Games and giving the studio free rein to create any game story it wanted so long as the core Little Sister/ Big Daddy game mechanic was kept intact. It wasn’t until Ken took a trip to the Rockefeller Center, witnessed its art deco aesthetic and learnt of the troubles the construction of the building faced that he was inspired to come up with the concept of Rapture and of its creator, Andrew Ryan – the game’s infamous antagonist and whose name is, in fact, a play on the author Ayn Rand’s name whose philosophical values of Obstructivism became core to the game’s narrative. Is a man not entitled to the sweat of his brow, and all that.

And in fact, this time around there was a much bigger focus on narrative and on telling a richer and deeper story than was the case with its spiritual successor of System Shock 2. «In normal games were just getting easier and easier to develop,» says Jon about the gap between the two Shock games. «For BioShock we were now using the Unreal Engine, but in System Shock 2 we were using the Thief Engine. I think we were the only other project that used it, so you can’t really say it was an engine.»

Power to the people

The switch to Unreal was advantageous because Irrational had experience with the engine, already having used it when developing SWAT 4 and Tribes. «So we had a lot of advantages in terms of knowing how to do things,» adds Jon, «so that allowed us to spend less time doing basic things and more time doing more complicated things, particularly on the narrative and scripting side of things. Which I think, after Half-Life, every first-person shooter had to start doing.»

By comparison, BioShock had considerably more scripted moments dedicated to narrative than any of System Shock 2, which Jon suggests, «Really only has a couple of those [scripted moments] and they’re a bit ropey. They’re well-written and stuff, but in terms of their animation and the way that they’re delivered, they’re a little laughable now.»

And by focussing on a console release as a priority, Irrational Games was able to address the concern that System Shock 2 had been too fiddly, too menu-driven and too complicated. This wasn’t just about introducing features to players in a more effective manner, but also in simplifying and minimising the interactions the player did outside of the gameplay. That’s where the idea for the feature-specific vending machines came about, allowing players to interact with a mechanic within the world rather than toiling away looking for the necessary option within a series of menus.

The Gatherer’s Garden is used for getting ability upgrades, the Gene Bank was for customising your ability loadouts, Power To The People for enhancing your weapons and of course the renombrado Circus Of Values was for stocking up on essential items. Perhaps it sounds more convoluted than a menu and its various sub-menus, but having each feature siphoned away to its own machine meant that not only were players engaged with the world of Rapture while even considering metagame facets like character upgrades but that everything was so much more approachable than the mouse-and-keyboard play of PC RPGs.

«The Psy system from System Shock we thought was underutilised,» adds Jon. «It was cool, but it wasn’t as essential to the game as we had wanted it to be.» This was why the Plasmid system became so important to both the narrative and the gameplay of BioShock, because Irrational had felt that it was too easy to overlook the cool mechanic within System Shock 2 which had been designed to allow for multiple replays with completely different styles of playing. «We thought this was kind of a waste, because most people don’t finish a game merienda, let alone three times. We wanted to expose players to these systems a bit more uniformly, so the Plasmid system in BioShock is more central to the game than the Psy system was in System Shock 2.»

It helped that the experience of creating the Psy System also meant that the team knew what to weed out when it came to powers and abilities in BioShock, too. «It’s a better design. I mean the Psy powers in System Shock 2, there are a few useful ones but there are a lot of them that are not that useful,» explains Jon. «Whereas the Plasmid System was designed with the benefit of having already built a system like that merienda, we could make sure those powers were more generally useful.»

Lasting legacy

«To me, BioShock is a fantastic game but the greatest achievement is that it proved that there was a market for that kind of game.»

Jonathan Chey

Throughout development, Irrational always held System Shock 2 up as a foundational goal, and with the financial backing of 2K Games giving the developer more scope to improve on absolutely every single aspect, it nailed it. «In my mind, what I had hoped BioShock would achieve was bringing a lot of those gameplay systems [from System Shock 2] to a larger audience. Ken obviously had a lot of narrative ideas that were important for him in the game, and I think he succeeded wildly with those too.»

And succeed the studio did. BioShock released in August 2007 on PC and as a console exclusive on Xbox 360 and was a huge success. Critics and players alike praised its narrative themes, RPG-infused gameplay and its iconic visuals, and it went on to win numerous Game Of The Year awards and quickly became a multi-million selling franchise. That doesn’t mean that there weren’t faults with the game, however, with some being more notorious than others.

«The boss fight is not our highest point in development,» admits Jon of how the latter part of BioShock kind of veers off-kilter. «I think we always found it hard to do endings. We knew we needed something at the end to wrap it all up. And I actually think this is true for System Shock 2 as well, I think the end of the game is the worst part of it. And part of the reason is that the end of the game has a lot of pressure to make it cool, and do some special things, and there needs to be a boss fight and there needs to be a totally new environment and you’ve kind of got to do all of this special case stuff.»

Jon adds that in a need to add some finality to the game, things «kind of get dumbed down» and that hit BioShock hard simply for the originality and engagement of everything that came before. Despite that, no one really remembers those final moments of BioShock, which says a lot of just how stellar the rest of the experience is. It was a combination of everything: engrossing gameplay with freedom of choice; a rich and unique world to explore; and a truly unique art direction for a videogame.

«To me, BioShock is a fantastic game but the greatest achievement is that it proved that there was a market for that kind of game,” says Jon. «I guess it created that market really. I think BioShock, compared to System Shock 2 and Deus Ex and Thief and Ultima Underworld and all the other games that we or Looking Glass and Warren Spector had made in that genre, BioShock was the first one that was a multi-million seller. After that, publishers were interested in that kind of game, and obviously 2K wanted to do more of it. I’m pretty sure it helped with things like the Deus Ex sequels, I think it helped influence a whole bunch of other games in that genre.»

It definitely did open up players to the idea that FPS games could be smarter, deeper and engaging beyond pointing the crosshairs at a Fascista’s head. «I couldn’t be happier with BioShock,» says Jon. «It’s definitely one of the things I’m most proud of in my game development career.»

This feature originally appeared in issue 237 (opens in new tab) of Retro Gamer magazine. For more fantastic features and interviews, you can subscribe to Retro Gamer in print or digital here. (opens in new tab)